Why I Started Alpine

You become your environment, so choose it carefully. I learned a few lessons early in my career and suffered a few Wall Street low points that shaped Alpine’s intentional, people-driven culture.

Wall Street Ambitions

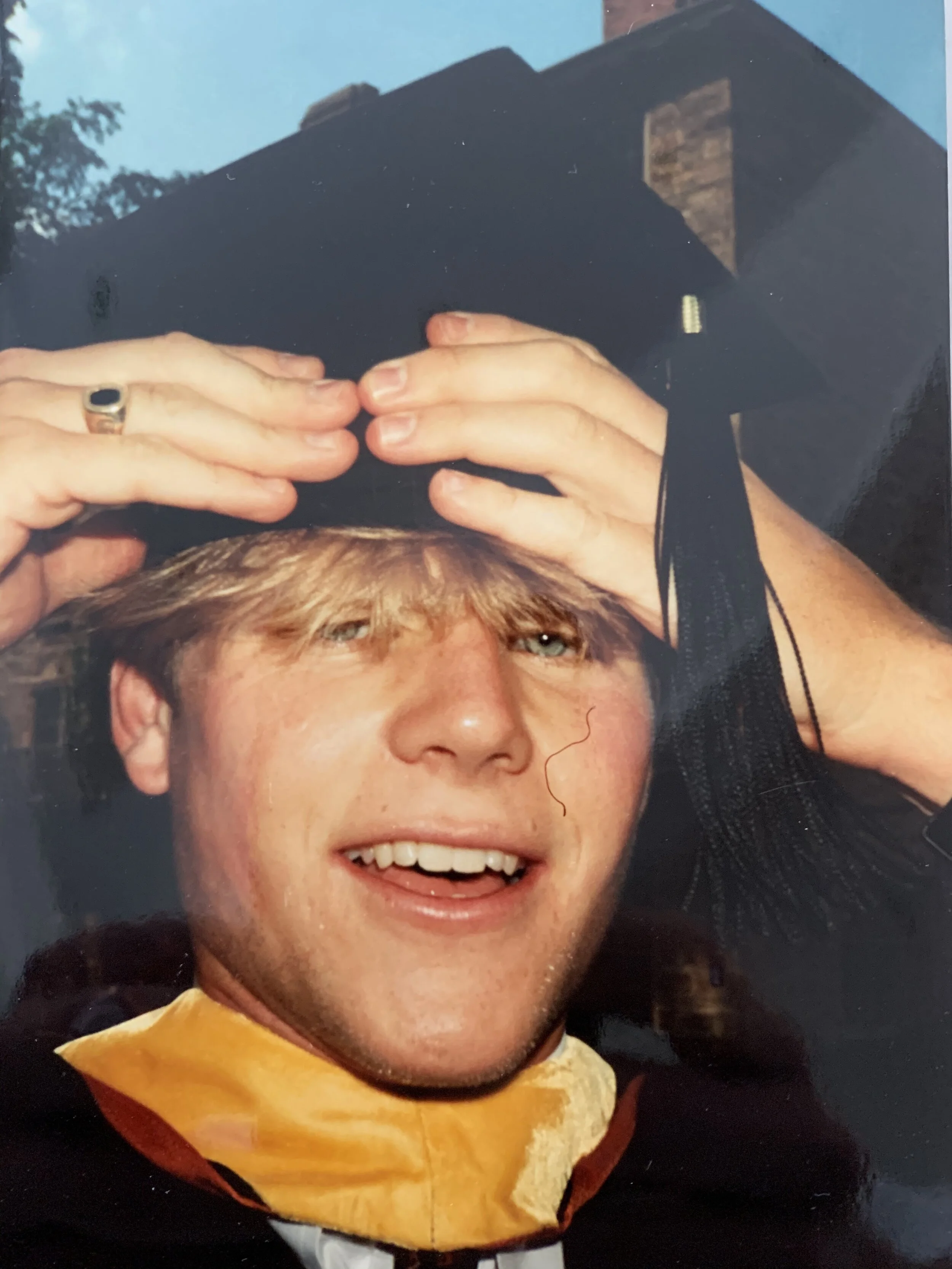

I graduated from college ready to take over the world. After pushing myself hard academically and athletically in college, I approached the workforce with confidence and excitement. And I had a job on Wall Street—the capitalist hub of the universe.

I went through a two-week training program with a group of 40 or 50 incoming analysts. The primary topic? How to use Lotus—the spreadsheet that preceded Excel—without touching the mouse. It turns out, you can build models a lot faster if you use a keyboard. I had a steep learning curve, for about two weeks.

For the rest of my two-year analyst program, I page-checked investment books for typos, built Lotus models, and formatted pages to make them look nice. Was this line too thick? Should I bold or underline the market cap and the IRR? Maybe a double underline for emphasis. Can I fit all of this on a single page? Repeat. For two years.

I reported to someone, we’ll call him Fred, who was about nine months older than I and though I have never been in a fraternity, I believe in his mind he was hazing me like a pledge for two years. Rather than make me shotgun stale beer or streak the campus, Fred wanted to see how little sleep I could get and how few hours I could spend outside of work—four hours per night and four hours per night, respectively.

Fred reported to an associate who we’ll call Joe. This guy was probably the most insecure guy in the firm. He was still young enough that he commanded no respect, but old enough that his superiors expected him to know what he was doing, and they had zero tolerance for his mistakes. Joe had a fiancé, or so he said. I never saw her and other than a week-long vacation to Mexico from which he was called back early, I don’t see how Joe ever could have seen her either. She was Wall Street’s version of Snuffleupagus, Big Bird’s imaginary friend on Sesame Street.

If Joe was in the office, then Fred had to be in the office. And if Fred was in the office, then I had to be in the office. Leaving before your boss was not tolerated. Embezzling copy paper, buying groceries with your meal allowance, or taking your girlfriend to dinner in a company-reimbursed black car were common practices—leaving before your boss was not. So the bottleneck to my going home was an insecure guy who was fighting for his job and didn’t seem to have much to go home to.

Joe didn’t really know how to use Lotus. He must have missed his two-week training or not been paying attention. More likely, Joe just wasn’t as bright as his resume claimed. So he would stand over my shoulder at my cubicle and “drive.” “Move up, no, go right. Change that number. No, not that one. Wait. Damn it. Go down.” Every so often I would get up from my desk and accidentally bump into Joe and shove him aside as I took a bathroom break, a small victory.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but Wall Street was changing me. At dinner, my fellow analysts and I compared the square feet of different peoples’ Hamptons homes and the sizes of bonuses we could get if we stuck it out. Money and material things became our goal posts, and winning the game became a function of tolerating sleeplessness and falling into line.

“Money and material things became our goal posts, and winning the game became a function of tolerating sleeplessness and falling into line.”

A Wake Up Call

The lowest point of my analyst program was one weekend when my mom came to visit. My mom lived in Ohio and saved up to drive out and visit her son in the big city. She had planned the trip for months and the itinerary included two Broadway shows, eating at different carefully-researched restaurants, and ice skating in Rockefeller Center. My mom was a single mother and the two of us were very close. I loved spending time with her and was really excited about her visit. I only saw her for four hours the entire weekend and missed most of her planned events. She explored Manhattan by herself. Almost worse than missing time with her, I felt like she should understand why I couldn’t leave the office; Fred hadn’t decided that he wanted to leave just yet.

Eventually, I escaped Wall Street to go to business school, a decision I nearly didn’t make. I deferred admission once and when I tried to defer the second time, the admissions director called me and told me she wasn’t going to let me in again unless I enrolled that year. At business school I was surrounded by people from different backgrounds with different goals. I had classmates who had been teachers, entrepreneurs, leaders in the military, professional athletes, and executives of nonprofits. As time passed and I spent more time with my classmates, I felt embarrassed by the person I had become on Wall Street. I had wasted two years of my life, but more frightening—I could have stayed on Wall Street and become that person permanently.

I apologized to my mom.

My experience on Wall Street highlighted the monumental role our environment plays in our lives. In short: We become our environment.

People First

Shortly after business school, I set out to start my own investment firm, Alpine Investors, a private equity firm built around people. Our investment strategy, our time, our energy, our money, and our resources all center around working with world-class talent. I asked myself, “What environment do we need to create at Alpine where the best people in the world will want to join because it’s a place where they can grow and thrive? I was very fortunate to bring on Danny Sanner, Billy Maguy, Will Adams, and Mike Duran right away—all shared and embodied Alpine’s vision.

For our first 12 years, we didn’t hire anyone who had ever stepped foot in an investment bank or worked on Wall Street. I reasoned that we could teach people investing faster than we could undo values Wall Street might have instilled.

Over the past 20 years we’ve made mistakes to be sure. But we have relentlessly focused on creating an environment where the best people want to come to work; where they can work with people they like, trust, and admire; where they can find an environment and leaders that help them grow into the best versions of themselves; and where they can have a meaningful life outside of work.

The Alpine team, 2020

My own life outside of work includes raising a family, teaching at Stanford Graduate School of Business, and living less than 15 minutes from my mom, who I get to see weekly. We’re making up for lost time!

My story of Wall Street may seem humorous or exaggerated, like I’m complaining, have an axe to grind, or have sour grapes. And maybe all of that is true. But mostly, I’m terrified to think about who I would have become if I had stayed.

You become your environment over time. You become your friends, role models, partner, work colleagues, and the institutions with whom you associate. With whom we share our lives determines who we become.

Choose them carefully. Not many things will make a bigger difference in your life.