How Walt Disney Demonstrated the Power of the “100/100 Rule”

In the early 1930s, a small film studio announced its intention to produce a full-length animated feature. There were many naysayers, including senior executives from the studio and many of the studio’s staff. As production continued, and dragged on for several years, nearly everyone in Hollywood “knew” the undertaking was a huge mistake, and many wrote the studio’s obituary. Up to that point, animated cartoons were limited to 8- to 10-minute gags shown prior to motion pictures. They almost exclusively involved animals because people were too difficult to draw, and it was common knowledge that it was impossible for an animated film to hold one’s attention for more than ten minutes. The $250,000 budget for the audacious studio’s full-length feature was considered absurd for an animated production. The actual production costs would exceed $1.3 million by the end, nearly 50x the cost of a short feature and the project would take nearly four years in the end.

Thirty years prior to this studio’s undertaking, an Italian economist, engineer, and sociologist by the name of Vilfredo Pareto noted when growing peas in his garden that around 80% of the peas were produced by 20% of the peapods. After finding several other examples of this dynamic, he generalized these findings to what is now called the Pareto Principle which essentially says that 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. Over the past century, the “80/20 rule” has been widely applied to business: 80% of sales come from 20% of customers, 80% of sales are made by 20% of salespeople, 80% of results generally come from 20% of the effort.

While Pareto’s law has had broad, wide, and significant implications throughout history, its application by Walt Disney in the production of Snow White in 1934—the story referenced above, in case you didn’t guess—was not one of them. When producing Snow White, Walt Disney applied the “100/100 rule.”

The 100/100 Rule

At Alpine, we coined the term “the 100/100 rule” for situations in which we commit to expend 100% (or more) of the work in order to come as close as possible to guaranteeing a 100% chance of success. We specifically contrast this to the 80/20 rule which focuses on minimizing effort and achieving efficiency. The 100/100 rule refers to maximizing effort and achieving the highest probability of success. Given the intensity of effort required in these situations, we reserved this classification for only the most important tasks.

In 2010 we were applying for a license from the Small Business Administration. After more than a year of work on the application, the final step was a one-hour meeting with the entire SBA executive team, after which we would either have access to capital from the SBA or be denied a license. It was all or nothing.

No amount of time was too much to invest in meeting preparation. We engaged lawyers who specialized in the SBA application process, and we conducted mock interviews and dry runs. We came equipped with every number imaginable and spent nearly 50 hours preparing for this meeting. Our preparation paid off and we were one of the first equity funds to ever qualify for an SBIC license.

Walt Disney and Snow White

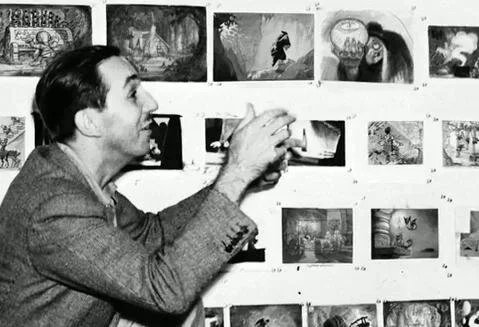

While Walt Disney never referenced “the 100/100 rule” specifically, the process by which he created Snow White embodies its application.

As described in the wonderful biography, “Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination” by Neal Gabler, Disney adapted the script for Snow White from a German fairy tale by Brothers Grimm. He recognized that the seven dwarfs offered opportunities to employ dozens of gags, which had become his hallmark in his previous short animated films, “Silly Symphonies.” Disney and his team came up with nearly fifty potential candidates for dwarf characters, including Jumpy, Deafy, Dizzey, Hickey, Wheezy, Baldy, Gabby, Nifty, Sniffy, Swift, Lazy, Puffy, Stuffy, Tubby, Shorty, and Burpy. The animators created hundreds of feet of footage of dozens of potential dwarfs knowing that most of that footage would never be used in final production. The team poured over every detail of the script—from which dwarf would cry upon finding Snow White asleep (Grumpy) to how many frogs would appear in the dwarf’s shoes (one).

Gabler describes Disney’s creation process, “… and always, as he had been doing for years now, [Walt] would recite the story to anyone who would listen. Anything from a short version to the full 3-hour performance… Walt was still telling the story in its entirety at a meeting every cut, every fade out, every line of dialogue. He was telling it all the time.”

Walt would act out every voice, every character and every plot nuance. Many animators estimate they have personally watched Walt act out the full length 3-hour several dozen times and that by the end he had probably performed the movie in whole or in part himself perhaps 100 times. Each time Walt would change a very small detail such as a plot twist or a character’s voice. Each time he would get input from the animators. Each time he would crystalize in his mind—and for the benefit of animators—precisely how the movie would play out.

Walt Disney was solving for achieving as close to a 100% probability that Snow White would be successful. He was committed to spending 100% (or more) of the energy to achieve this goal. Disney devoted the majority of his studio’s animators to the production of Snow White, despite the fact that it would produce no revenue for the studio for several years. He established a line of credit with Bank of America and set a budget for the picture that ensured he would have ample capital and, most importantly, time, to produce the picture to his exacting standards.

His commitment to the film’s success and the resources he applied to its success never wavered during the four years of its production. Walt Disney and his animators not only willed Snow White to succeed but, through their commitment to the production, they virtually guaranteed it would.

Leaving a Legacy

The world’s first ever, full-length animated feature, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” opened on December 21, 1937 to rave reviews. Snow White did not just introduce the world to a full-length animated film, it revolutionized animation. It was the first animated movie to have full-length original musical scores, multi-dimensional characters, intricate scenes, and nuanced plot development. The film went on to gross more than four times any other film in 1938, and despite being introduced during a horrible economic period in an era where there were a fraction of the movie theatres there are today and no DVDs or Netflix, as of 2019, Snow White ranked as one of the top ten box office performers of all time, adjusted for inflation.

Would the entire industry of full-length animated films exist today had “Snow White” never been produced? Films like “Finding Nemo,” “The Lego Movie,” or “Frozen” stand on the shoulders of “Snow White.” And “Snow White” stands on the shoulders of Walt Disney’s four year commitment to its success.

The 100/100 rule is a commitment to do whatever it takes to achieve a specific goal. The magic of the designation is that it allows crystal clear prioritization for the entire organization and importantly gives people permission to drop less important tasks. It takes intention to recognize which very special goals qualify for this designation, and it takes courage, patience, and discipline to stick with these goals and give your team permission to forgo others in order to hit them.

“The 100/100 rule is a commitment to do whatever it takes to achieve a specific goal. The magic of the designation is that it allows crystal clear prioritization for the entire organization and importantly gives people permission to drop less important tasks.”

Walt Disney demonstrated this process for four years in his studio’s commitment to Snow White. What matters that much to you?

Take it from one of the successful greats, if you are going to attack an inspiring and audacious Genie-inspired goal, you can significantly increase your probability of achieving it by employing the 100/100 rule.

The 80/20 rule is a minimization equation. In this equation, one sets the goal of attaining 80% of a given result and is solving to do so with the least effort. A minimization equation like the 80/20 is designed to create efficiency. Efficiency is defined as the ratio of useful work performed by a machine or process to the total energy expended, so the denominator, total energy expended, matters.

By contrast, the 100/100 rule is a maximization equation. The focus is on attaining 100% of the potential result and doing so with as close to 100% probability as possible. In this equation, we are not concerned with minimizing effort. Conversely, we are almost certainly going to waste energy because conserving energy is not an objective. The 100/100 rule is designed to create an endogenous outcome. An endogenous outcome is an outcome that is not attributable to an external or environmental factor. It is an outcome created by and contained within the endogenous process you will create. In other words, the 100/100 rule is designed to help you create a process which leaves nothing to chance.

To be clear, virtually nothing can be achieved with a 100% probability, particularly an audacious, Genie-inspired goal. But by committing to the 100/100 rule we can get as close as possible to creating endogenous outcomes.

“In other words, the 100/100 rule is designed to help you create a process which leaves nothing to chance.”