When My Oldest Child Left for College, I Had to Learn to Let Go.

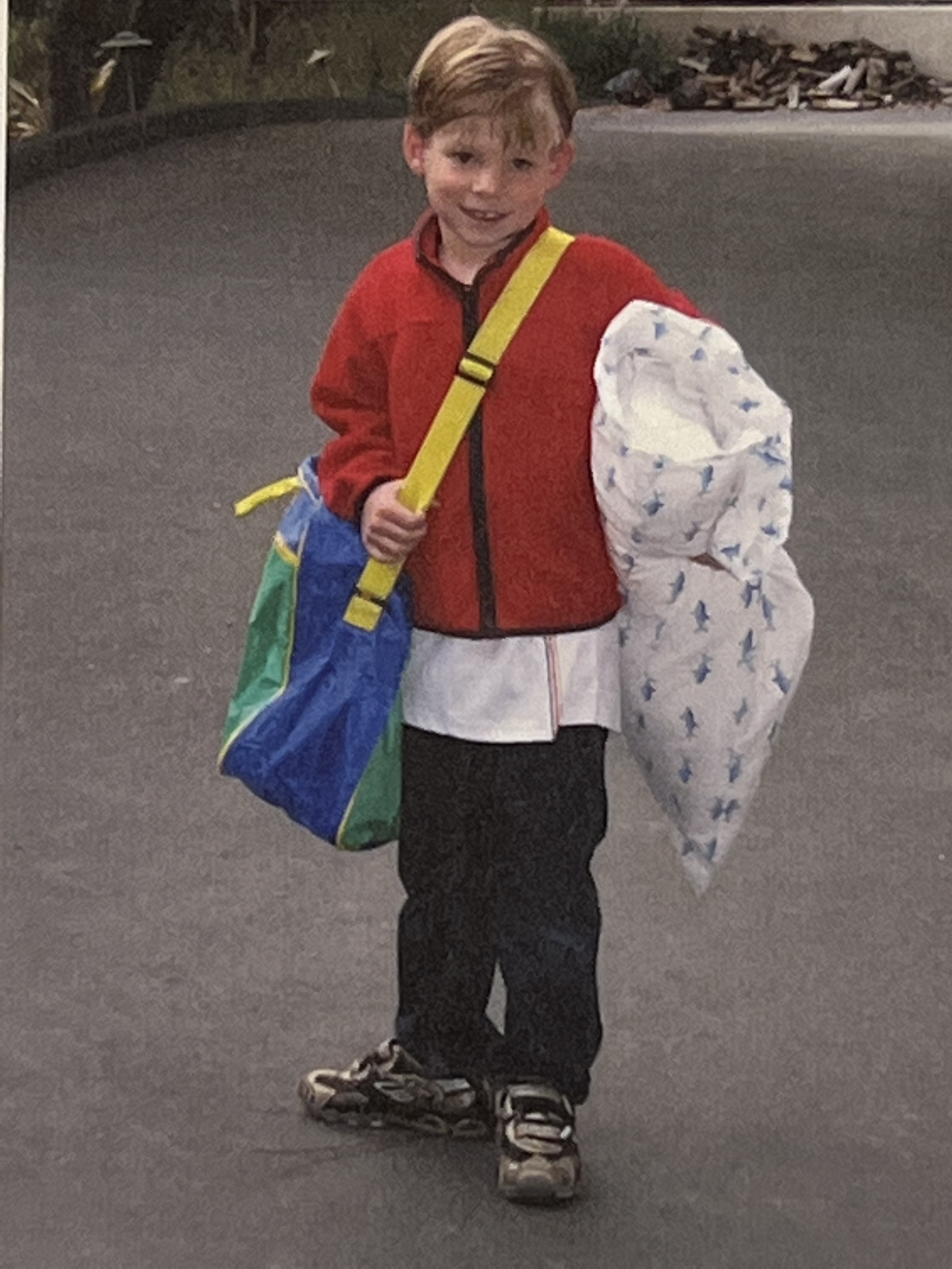

Chase. Age 5. His first sleepover (at Grammy’s house).

Chase. Age 18. His first night of college.

Cindy and I were going to be exceptional parents. We vowed that none of our kids would watch TV, own an iPhone, or eat junk food. They would eat only organic fruits and vegetables, learn three languages by age six, play multiple instruments, and read Tolstoy and Hemingway.

After knocking out one of his opponents in 80 seconds, heavyweight champion Mike Tyson was asked how he contended with his opponent’s pre-fight plan. Tyson famously responded:

“Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

And so it was with our parenting.

Chase, Lily, and Blake

At one point, we had three kids under the age of five. Our newborn Lily was still waking up in the middle of the night every few hours while her older brothers, Chase (5) and Blake (3), were full of energy all day. We never got their nap schedules to align, so, except for a few hours at night, at least one kid required attention 24/7. Out of necessity or lack of will, we replaced organic foods with Goldfish crackers, realized "The Wiggles” held a three-year-old’s attention better than “Mandarin-For-Kids,” and settled for peace and quiet when we could find it over pushing “War and Peace” on our kids.

We had so many amazing moments with the young kids, but without the videos and photos, I’m not sure how much I would remember. It was a beautiful blur.

I started Alpine Investors two years before our oldest son Chase was born. Layered on top of those early years of sleep deprivation were my most stressful years at work. Our first fund lost money, which is not how I would recommend starting out of the gates. Several years later, as we began to dig out of that hole, Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, wreaking havoc on the entire financial system — and Alpine along with it. Lily was born ten days later.

My kids were oblivious to all of it. Each evening as I pulled into the driveway, the older boys would sprint (or, in the two-year-old’s case, waddle) out to the car, screaming, “Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!!!!” One such evening, I was finishing a phone call with an older friend. He heard all the commotion, and I told him I’d have to call him later. I remember his words so clearly: “Enjoy that, Graham. It will pass quickly.”

When you’re in the moment, sleep-deprived, and it’s your turn to get up from your much-needed rest, change Chase’s diaper, feed him, and sit with him until he falls back to sleep as you watch the clock counting down the minutes until you need to work during the financial crisis … it doesn’t feel like it’s going by quickly.

But time is like an avalanche. It starts slowly — a snowball barely moving down the hill. But as it gathers speed, it also gathers momentum. Every older parent tells the younger parent, “It goes by fast,” because experience has forced them to realize that each phase with your kids will only happen once. You can’t roll the avalanche back up the hill. It will inevitably take everything in its path, including not only your own youth — but also your children’s.

I fought hard against the ever-intensifying avalanche. I drove the kids to the bus and waved as it drove away, their little hands in the window waving back. I read the same three books they requested over and over (for what seemed like years). I built tree forts and zip lines, the latter ending in a trip to the ER. We rode bikes, threw, kicked, and hit balls, made obstacle courses, and raced each other. We lugged all five of us across the country for family vacations and had dinner at six o’clock every night in the dining room. I went to school plays, swim meets, tennis matches, and basketball, lacrosse, and soccer games too numerous to count.

But the avalanche was relentless.

The bikes in the garage turned into a shared car as the older boys got their driver’s licenses. We often had ten or more hormone-filled teenage boys in our living room. “Sup, Mr. Weaver?” was the refrain as they walked past me to ravage our pantry. And those were the good nights. The other nights, the kids went “out,” returning home well after my second REM cycle.

I started to realize that while my oldest son, Chase, was technically living at home, he was already separating from us. While a normal and healthy process for an adolescent, it still stung that he was finding his identity outside of the family. Chase would join our family dinner — making a point to spend time with us — while his phone dinged with texts from his friends.

His final year at home was the hardest. Everything happened as it had in the past 18 years, only this time, each event was the “last.” I fought with all my might, trying to hold onto the last back-to-school night, his last birthday at home, his last tennis match, and then finally, his last week living at home. During this time, I often replayed the prior 18 years and constantly questioned if I had been a good enough parent. Could I have attended more events, spent more time with him, or offered better advice? Were we still going to be close once he was no longer confined to our home and obligated to spend time with me?

At our last family dinner in the dining room, we each wrote Chase a letter about what he meant to us. Blake and Lily’s letters blew me away. It was clear the three kids were incredibly close, and Chase’s leaving was just as hard on them as it was on Cindy and me. All five of us cried. As tough as it was, we will never forget that night. We all got much-needed closure.

We flew down to help Chase get settled in as a freshman at San Diego State. We made nine trips to Target and Staples — perpetuating, if only for a few more hours, the feeling that he needed his parents. But there was only so much we could do to fortify a 420-square-foot dorm room, and eventually, we had to say goodbye.

And then like that, he was gone.

Chase being away from home hits me at different times. Even though only 20% of the family left the house, it is somehow about 85% quieter. Each time I pull into the driveway, I see his bike and remember him at two, learning to ride, and later mountain biking with him on weekends. Every morning, the door to his room is open, and I am again reminded that he doesn’t live here anymore. We haven’t had a family dinner in the dining room since he left – we moved to the kitchen. It’s unspoken, but none of us wants to sit across from his empty seat every night.

I could pass along cliché advice like “Enjoy the moment” or “It goes quickly.” And that would be good advice. So, yes, do that!

But my more valuable and counterintuitive advice for parents is to learn to let go. The cascading avalanche of time marches on, altering every landscape. The harder we try to attach to our current situation, the more painful it will be when it inevitably changes.

Perhaps instead, time’s unwieldy progression is a gift working for our benefit, clearing a path with new adventures waiting for us. And maybe we just need to surrender and let go, allowing each moment to unfold and embracing each new phase of life. Though we might have become accustomed to the prior landscape, life has a way of opening new magical experiences for us. As Michael Singer writes in his book, “The Surrender Experiment”:

“I was not in charge, yet life continued to unfold as if it knew just what it was doing.”

Rather than the fruitless effort of trying to stop the avalanche of time, maybe we are supposed to jump on a sled and enjoy the ride.