How Applying the Principles of Lean Manufacturing Transformed Alpine

Adapted from my speech at Alpine Investors’ 2024 Growth Summit.

Japan’s economy was in turmoil following World War II. GDP declined to less than half [1] of its pre-war peak, industrial production dropped a staggering 72%, and nearly three-fourths [2] of the nation was living in poverty. It was at this dire, pivotal moment that the country’s history took a surprising and incredible turn.

From 1950 to the mid-1970s, Japan’s economy went on a tear, growing an average of 8% per year [3] — outpacing the GDP growth rate of nearly every other developed country and ultimately making Japan the second-largest economy [4] in the world. The phrase “made in Japan” went from being synonymous with cheap and unreliable, to being a symbol of excellence, precision, and quality.

When you trace the origins of this remarkable transformation, most of the threads lead to a turnaround in Japanese manufacturing. And many of the roots of that manufacturing turnaround come from one man: Edward Deming.

Deming was the American statistician, economist, and business theorist initially tapped to help prepare for Japan’s 1951 census. He ultimately used his expertise to train hundreds of Japanese engineers and managers in a production process called statistical quality control — which was foundational for systems known today by many other names, including the Toyota Production System, Six Sigma, the Danaher Business System, and Lean manufacturing.

“Lean” has become the foundation of excellence — and countless comebacks — for companies all over the world.”

Alpine is one of those companies. In 2008, we were facing a crisis of our own. The global economy had cratered, the stock market was down 55%, we had multiple companies in default on their credit agreements, and we were making no progress in our attempts to raise our fourth fund. But fortuitously, we met a coach named Tom Vocolla. Similar to Deming’s coaching in Japan, Tom taught Alpine’s team the core principles of Lean manufacturing and helped us apply them to the private equity business.

Lean Manufacturing (Alpine’s Version)

The words “Lean manufacturing” are similar to words such as “strategy,” “culture,” and “leadership” — ask 10 people what they mean, and you’ll get 10 different answers. But in hopes of providing some foundational takeaways that you can quickly apply to your business, no matter the industry, I want to simplify it dramatically. Think of this as “Lean Manufacturing (Alpine’s Version).”

The basics of Alpine’s Lean boil down to three principles:

Carve out time to work on your business.

Map your core processes.

Continuously improve (kaizen).

Principle 1: Carve Out Time

The first principle of Lean manufacturing is the least complicated, but by far the most important — because without it, you will never execute on the other two. Tom helped us clarify the distinction between working “in” the business and working “on” the business. Working “in” the business is about the core functions of your company. In our case, this means sourcing, evaluating, and closing deals; serving on boards; hiring executives; etc. Working “on” the business means you are stepping back, looking at your business from 10,000 feet, and implementing ways to improve it. Working “on” the business is extremely rare, but it is the single most important part of Lean manufacturing, and, as far as I know, the only path to becoming the best in the world. If you take one lesson from this post, let it be that you must set aside time — every week — to work “on” the core parts of your business.

“If you take one lesson from this post, let it be that you must set aside time — every week — to work ‘on’ the core parts of your business.”

That’s easy to say, but much harder to do. When you’re running a company, it’s all too easy to let the urgent crowd out the important. So, how do you do this? Start with your calendar. Carve out two to four hours per week with the right people to work on the two principles that follow. I promise, if you do this consistently, you will look back years from now and realize these hours were the most valuable use of your time.

Principle 2: Map Your Processes

Deming once said, “If you can't describe what you are doing as a process, you don't know what you're doing.” Anything that happens in your business can be broken down into small, discrete steps, and each of those steps can be improved and optimized.

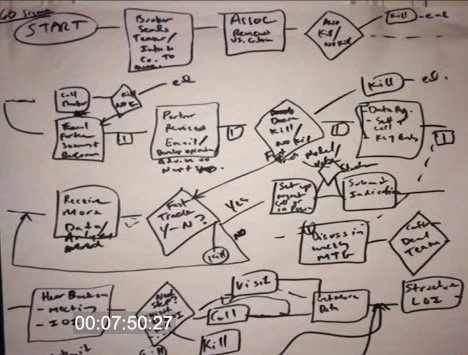

At Alpine, our first process map covered the time between a potential deal coming into the signed letter of intent (LOI). This was our first draft:

It was a mess — and even the mess was optimistic! In reality, we had a dozen different processes, which changed depending on everything but the weather: where the deal came in, who had time to handle it, and a partner’s unique deal process that day might all impact what happened next. But reconciling multiple approaches is a key part of process-mapping. You’re figuring out the best version and getting everyone aligned around it. We spent half a day moving around Post-it notes, and eventually ended up with a rectangle for each activity, a diamond for each decision, and flow lines for each “yes” and “no” decision.

“In reality, we had a dozen different processes, which changed depending on everything but the weather: where the deal came in, who had time to handle it, and a partner’s unique deal process that day might all impact what happened next.”

Crucially, we also identified a single person who would be accountable for each step — because if you’ve ever tried to assign a decision or task to a team, you know it is a recipe for getting nothing done. Having a single owner for every part of the process speeds things up dramatically because it facilitates empowerment, which is a foundational principle of Lean.

When we first laid out our pre-LOI process, the decision of whether to visit a company had three flow lines: yes, no, and “we don’t know yet.” We realized 80% of our deals were getting stuck in that last category, which created a lot of work for our small team. More importantly, it meant that we weren’t moving quickly enough to win the most desirable deals. Upon learning this, we eliminated the indecisive option. When a deal arrived, there were only two paths: kill the deal or visit the company in the next seven days. We dubbed this our “pass or sprint” framework. This one change was revolutionary; we quintupled our capacity, cut our time on deals that didn’t close by 90%, and started winning the deals we wanted most.

“This one change was revolutionary; we quintupled our capacity, cut our time on deals that didn’t close by 90%, and started winning the deals we wanted most.”

Sometimes, while creating a process map, you discover that what you thought was a step is actually a process of its own. This was true for us with management visits, which had a higher conversion rate when I was involved. We realized this wasn’t magic or good luck; it was simply that I was following a different process. So we did another process map, breaking each management visit into a series of detailed steps including “researching the team,” “selling Alpine,” “understanding the owners’ needs,” and “following up.” Today, this process is known as Alpine’s “Win the Deal” playbook, and it’s increased our win rate on sprint deals to 80%.

Process-mapping isn’t rocket science, but just like setting aside regular time to work on your business, it can be pretty tedious. If you have the discipline to do it anyway, you and your team will reap the rewards.

Principle 3: Continuously Improve

Once you’ve mapped every step in your process, you can optimize each one — and if you do that again and again, you will become the best in the world.

Like Lean manufacturing itself, continuous improvement goes by many names. At Toyota, it’s known as kaizen; at Alpine, we call it “opportunities for improvement,” or OFI. To me, the simplest way to define an OFI is to identify an important question you don’t know how to answer. “How do we reach an 80% close rate on software demos?” “How do we double our management visit success rate?” “How would we design a program to train CEOs?”

“The simplest way to define an OFI is to identify an important question you don’t know how to answer.”

These are questions where you don’t yet know the “how,” because “how” is the killer of all great dreams. Setting an OFI allows you to dream without a dark cloud of “how” stopping you in your tracks.

How do you know where to focus your next OFI? I recommend you put an “X” on the most critical step of your process map, then try to improve it by two standard deviations (or more).

Southwest Airlines is one of my favorite examples of this principle’s power. In the early 1970s, after spending years fighting off a lawsuit from competitors over their low prices, the company emerged victorious — but had $143 left in the bank [5]. Chairman Herb Kelleher knew they would have to sell one of the company’s four planes to survive, and he directed VP Ground Operations Bill Franklin to revamp the schedule for a fleet of three planes. Instead of cutting flights, Franklin came back with the same schedule — and a plan to cut gate turnaround time [6] from 65 minutes to 10 minutes.

This became Southwest’s “X.” Every single thing they did, from replacing catering with peanuts and water, to unassigned seating, to eschewing a traditional hub-and-spoke business model for point-to-point flights, was designed around the goal of the “10-minute turn.” Eventually, they achieved it — and became the top-performing stock [7] on the NASDAQ over the 30-year period from 1972 to 2002.

Tesla has also used Lean principles to outdo its competitors. Elon Musk reportedly spent years sleeping on the floor [8] at the company’s factory in Fremont, California, during the launch of the Model 3. As the story goes [9], he went through most of the car’s 10,000 parts one by one, exploring how each could be made faster or more cheaply, or even eliminated entirely. Like the other principles of Lean manufacturing, continuous improvement can be tedious — and Musk’s infinite capacity for tedium enabled Tesla to sell what would have been an $80,000 car for $50,000, making it the world’s top-selling [10] electric vehicle.

Lean manufacturing also facilitated the rise of another of Musk’s companies. While it’s true that Lean is more about dedication than rocket science, sometimes it’s both: The same process Tesla followed on the Model 3 brought the costs of SpaceX rocket launches as low as $67 million [11], compared to $2.5 billion [12] for NASA’s Space Launch System.

What Are Your Bright Spots?

One more note on choosing your “X”: Think about the things your business is best at and how you can scale them. Maybe your bright spot is a salesperson who is amazing at closing, or a customer who is buying up all of your products, or an acquisition channel with a 10-to-1 LTV to CAC. At Alpine, the areas where we’ve doubled down most are add-on acquisitions and talent. Our CEO-in-Training program started with one person, then three — and because it was a home run, we kept on growing it. We’ve scaled our CEO-in-Residence program and our direct sourcing program the same way.

Humans are loss-seeking creatures; it’s in our nature to try to fix things that are broken. But if you instead put your focus on what’s working, the things that aren’t working shrink over time — and your strengths become all the more powerful.

“If you put your focus on what’s working, the things that aren’t working shrink over time — and your strengths become all the more powerful.”

Don’t Wait for Crisis

In both postwar Japan and the early days of Alpine, it took a crisis to catalyze change. Why? Because when you’re facing a crisis, the important suddenly becomes the urgent as well. On the brink of bankruptcy, Japan was willing to try anything — and, in the process, planted seeds that throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s became massive oak trees. Japanese companies set the global standard for quality.

But eventually, in the absence of the emergency, they sat in the shade of those trees they’d planted. In 1989, the country’s stock market value represented 45% of the world index [13], but it’s just 5% today [14].

Before the recession, all of us at Alpine were working extremely hard, but our strategy and capabilities were undifferentiated. When Tom Voccola introduced us to Lean, everything changed. It helped us become several standard deviations better than our competition on the things we do best, and the size — and performance — of our funds has grown exponentially since. Our turnaround was possible because we were dedicated to carving out time to work “on” the business and doing the tedious work of getting a little bit better every day.

Carving out time, mapping your processes, and continuously improving aren’t optional. They make your economic engine go. The magic is not waiting for a crisis to create urgency, and starting this important work — go ahead and put it on your calendar.

“Carving out time, mapping your processes, and continuously improving aren’t optional. They make your economic engine go.”

And there’s no time like the present. As the Chinese proverb says, “The best time to plant an oak tree was 20 years ago. The next-best time is now.”

Endnotes

[1] Nippon Communications Foundation: Lessons from the Japanese Miracle: Building the Foundations for a New Growth Paradigm

[2] Our World in Data (University of Oxford): Share of population living in extreme poverty, 1820 to 2018

[3] Our World in Data (University of Oxford): GDP per capita, 1950 to 1973

[4] The Asahi Shimbun: Japan’s GDP falls behind Germany to fourth place amid weak yen

[5] Justia: Wilson v. Southwest Airlines Co., 517 F. Supp. 292 (N.D. Tex. 1981)

[6] NPR: The Man Who Saved Southwest Airlines With A '10-Minute' Idea

[7] CNN: 30-Year super stocks

[8] Business Insider: Elon Musk says sleeping on factory floors was important so Tesla employees would 'give it their all,' days after a Twitter boss was pictured sleeping in the office

[10] Teslarati: Tesla Model 3 captures 72% of 2020 deliveries, dominates global EV market

[12] NASA: NASA’s Transition of the Space Launch System to a Commercial Services Contract

[13] Man Group: Japan: Opportunities in the Forgotten Equity Market

[14] Morgan Stanley Capital International: MSCI World Index Fact Sheet